-🏴☠️-Short Story-🏴☠️-

The Bench

The bench was old. The wood groaned under the weight of time or maybe just under me, sitting hunched and tired, staring out over the gray stillness of the bay. Waiting for ships to pass that never do.

The air smelled of salt and rusted iron. Seaweed clung to the rocks below. A tide rolled in without urgency. Just the slow, steady breathing of something ancient.

A figure came and sat beside me. I hadn’t seen him in years. Like an old friend. But this time, it was different.

Death adjusted his jacket, though the ocean wind never touched him.

“You were taller the last time I saw you,” I said.

He tilted his head. “And I thought you’d be angrier, since the last time.”

A dry laugh escaped my throat. “What’s the point? I’ve spent a lifetime fighting ghosts. You’re just the one who stuck around.”

“You lasted longer than most.”

“I was always told I was hard headed.”

“Yes,” he said. “You are.”

I glanced down at my hands, weathered, scarred, the same hands that once held a line against the pull of something bigger than me. “Do you always come in person?”

“No,” Death said. “Only when asked politely.”

“I remember now,” I murmured. “I whispered it, didn’t I?”

“You did,” he said softly. “At her funeral. When your hands wouldn’t stop shaking, and you realized you’d never say ‘goodnight’ again.”

We sat in silence. A raven floated overhead but didn’t cry. The wind moved through the dried grasses like it was searching for something it had lost.

“Will it hurt?” I asked.

“No more than it did to keep going,” he said.

I stared at my boots. “That much, huh.”

“Yes. But only for a moment.”

“You know,” I said, “I used to think people feared you because you were the end.”

“And now?”

“You’re just the quiet after the storm.”

He nodded. “I’m a mirror. Most don’t like what they see.”

I smirked. “And what do you see in me?”

Death studied me for a long time.

“A broken man, that carried on anyway. A man who stayed long after others left. A man who carried more than his share. A man who loved with a fierceness that burned through the fog. You didn’t say it often, but when you did… it meant everything. You held the line, even when no one saw. And when they left, you stayed. Not because you had to but because that’s who you are.”

I let out a long breath, drawn from somewhere deep. “Then I guess it’s not such a bad day to go.”

“No,” he said. “It’s a beautiful day to be done.”

I stood with the effort of old bones. My knees cracked. My spine complained. “Do I walk with you?”

“If you like.”

We walked to the edge of the water. The tide whispered against the rocks. Buoys clinked in the distance. This bay had held pieces of my life I’d never get back and I was finally ready to leave them where they belonged.

At the top of the bluff, the sky turned to stained glass. The sun caught the edge of the world on fire.

“Will I see her again?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Death answered. “But I do know, you’ll stop missing her.”

I smiled, a small, weathered thing.

I looked towards the horizon one last time. “That’s enough,” I whispered.

Then I closed my eyes and imagined her smile, one last time. “Goodnight, my love.”

Then I vanished. Not into light. Not into shadow. But into a soft exhale of the tide.

-🏴☠️-Essay-🏴☠️-

Death

We all have a name for it. A word we whisper, fear, sanitize, or dress in myth. Even today, it seems most people misspell it on purpose to skirt the algorithm, "unalive," as if saying the real thing might get them shadow banned. Deemed too offensive, too harsh, too real. Every language tries to define death, as if naming it will make it less inevitable. As if the right word might somehow keep it at bay.

English: Death — clinical, curt. The final entry in a medical file or casualty report. A term scribbled into official forms when something irreversible has occurred.1

Arabic: Al-Mawt — a sacred transition, often laced with divine will. It carries weight, not just of ending, but of destination.2

French: La Mort — a feminine shadow, romanticized and mourned with poise. It drapes itself in black lace, walks slowly, and whispers softly.3

Old Norse: Dauði — not feared, but honored. Death earned you a seat among ancestors, or cast you into forgetfulness if you died without honor. It was a gate, not a punishment.4

Mine: Death is the quiet partner that walks beside me every day. It doesn’t speak, doesn’t explain. It waits. Not with malice, but with certainty. Like a shadow that never leaves. Like breath on the back of your neck during the quiet moments when you're finally alone with your thoughts.

We name death in an attempt to understand it. But what we’re really doing is bargaining, trying to control something we never could. Hoping that if we can define it, maybe we can delay it. Maybe even outsmart it. We build myths, craft rituals, write poems, and raise tombstones not to conquer death, but to contain it. To make it smaller than it really is. But it never is. The names change. The fear stays the same.

Equality

Death doesn’t care.

It doesn’t care about your rank, your paycheck, your politics, or your plans. It doesn’t ask if you were a good father or a shitty human being. It doesn’t pause for prayer, privilege, or pity. Death shows up when it wants to. And when it does, it makes everything else look like background noise.

In a world obsessed with identity, status, and control, death is the only thing that levels the playing field. It’s the original equal opportunity enforcer. Doesn’t matter if your ancestors were kings or convicts, death erases the crown and the sentence in the same breath.

There’s irony here. We pour billions into Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs. We build policies and movements around the idea that life should be fair. But death has always been the most inclusive force in the universe. It doesn’t need a task force. It doesn’t publish statements. It just is. And it comes for everyone. Death gives us the only kind of equality that truly exists, one that doesn’t ask, doesn’t bend, and doesn’t miss.

As Camus wrote: “They were assured, of course, of the inerrable equality of death, but nobody wanted that kind of equality.”5

Because deep down, we don’t want fairness, we want to matter more than the next guy. Death doesn’t allow that. It comes with no preference and leaves no room for negotiation.

You can fight it, delay it, deny it. You can meditate, medicate, or pray. You can eat clean, run marathons, and fill your home with crystals and clean air. But when it’s your time, death doesn’t check your credentials. It just collects.

And when it does, all the stuff you thought mattered, your job title, your likes and followers, your salary, your resume, burns down to one simple fact: you were here, and now you’re not.

That’s the truth most people run from. Not because death is violent, but because it’s indifferent. And in a world that begs for validation, nothing stings worse than indifference.

Remembering

If death is the great equalizer, then remembering is how the living try to push back against that equality. It’s how we pretend some lives mattered more than others. Statues. Headstones. Eulogies. Honors. The United States is home to approximately 145,000 graveyards and cemeteries. Cemetery land in the United States occupies approximately 140,000 acres. Conventional cemeteries bury an average of 1,250 bodies per acre, while natural burial cemeteries generally accommodate hundreds per acre. We don’t just bury the dead, we elevate them. Or we erase them.

But none of it changes what happened. They're still gone.

Still, we’ve always done it. From the first human to carve a symbol on a cave wall for the fallen, to the billion dollar funeral industry that exists today, we mark the passing. We shape grief into ritual, and ritual into meaning.

The Romans understood this well. Especially among the aristocracy, families created imagines, wax masks molded from the faces of the dead and displayed in the front halls of their homes.6 These weren’t just memorials. They were moral compasses, reminders of legacy and duty. At funerals, actors would wear these masks, marching through the streets to honor the lineage. One legend even tells of Brutus, convinced by his mother to betray Caesar by pointing to the cast of his ancestor Lucius Junius Brutus, the man who helped overthrow the Roman monarchy generations before. Whether true or not, the story shows how remembrance could become obligation.7

In Japan, many homes hold a butsudan, a family altar for the dead. These aren’t relics or décor. They’re active spaces. Relatives talk to the deceased daily, leave food or tea, and include them in life’s moments. Death there is not the end of a relationship, it’s just the start of a quieter one.8

In Madagascar, the Malagasy people practice famadihana, or “the turning of the bones.” Every few years, families dig up the remains of their ancestors, rewrap them in fresh cloth, and dance with them through the village. It’s not morbid, it’s joyful. Ancestors are part of the community. Honoring them this way ensures they stay involved and remembered.9

The Aztecs had a deep reverence for death, which continues in the modern Día de los Muertos in Mexico. They believed the dead returned to visit, so families built altars, ofrendas, with food, drinks, and personal items. The dead are celebrated, not feared. You keep them alive by remembering who they were and what they loved.10

Among the Celts and ancient Britons, Samhain marked the thinning of the veil between the living and the dead. Spirits returned, not to haunt, but to visit. Fires were lit to guide them. Food and drink were left out to honor them. Death was part of a cycle, not an ending. You didn’t lose someone, you just couldn’t see them anymore.11

Even in Victorian England, people clung to memory in intimate and eerie ways. Hair was woven into mourning jewelry. Photographs were taken of the dead posed like they were still alive. These acts weren’t seen as morbid, they were desperate attempts to hold onto presence a little longer. To say, you mattered, and you still do.12

And in Tibet, death takes on another role entirely. In the practice of sky burial, bodies are placed on mountaintops and left for vultures to consume. The body is seen as a vessel, nothing more. Returning it to nature is the final act of generosity. The dead are not preserved, they are released.13

Even today, we build walls etched with names. We fold flags with precision, hand them to mothers, brothers, daughters, and say “Never forget,” like those words will somehow freeze time. But the truth is, most names fade within a generation.

I have my grandfather’s burial flag. He passed at a good age, after a full life. Next to it sits another, his brother’s, a gold star flag. He was killed on D-Day +24, during the Battle for Saint-Clair. One man came home. One didn’t. Both are remembered. But only because someone still chooses to remember them.

So no, I don’t mock tradition. I don’t dismiss the rituals or the folded flags or the quiet visits to a grave that nobody else remembers. I’ve stood there, too. I’ve felt the weight of memory pressed into cloth. I’ve stared at those flags and wondered what parts of them live in me. I honor them. I practice the traditions. But I also recognize the strange truth underneath it all.

Across all cultures, all faiths, all nations, death has a way of leveling us. It strips away the surface differences, the traditions and languages, the grudges and borders. And what’s left is a shared silence. A universal ache. A recognition that no matter how different we may seem while alive, in death, we are made equal.

So why do we remember? Is it about honoring the dead or protecting ourselves from the truth that soon, we’ll be next?

Maybe it’s both.

Maybe remembrance is the living’s way of convincing ourselves that death isn’t a full stop. That’s why we tie it all back to remembrance. Because as Achilles once said or at least in the retellings, “You truly die only when no one remembers your name.”

It’s not biological death that ends us. It’s silence. Obscurity. The moment when there’s no one left to whisper your name into the world.

But maybe, just maybe, it’s also a desperate attempt to keep the illusion of control. Because if we can tell the story of the dead, we can pretend we’ll get to write our own ending too.

But remembrance is a strange thing. We inherit it, we perform it, and eventually, we fade into it. Some are remembered for their names. Others for what they did. Most, for neither. The rituals stay, but the details blur. And knowing that, knowing that even the best stories dissolve over time, forces a different kind of question.

How I Want to Be Remembered

If we all vanish eventually, how do I want to be remembered?

Not as a name carved in stone, not as a folded flag on a shelf but as something useful. Something that lingers in a way that doesn’t ask to be noticed. I don’t want a statue. I don’t want my name on a plaque or a folded flag in a shadowbox. I’ve seen too many of those gather dust while the people left behind slowly forget how to smile.

I thought on this for awhile, while researching for and writing this essay. Then the other night while watching Braves baseball, a specific example hit me. The play by play caller, Brandon Gaudin14, does a great job of pretending he has all of baseball history stored in his brain, as if I don’t know there’s a computer feeding him every stat in real time. Still, he sells it well.

Brandon was pulling up a stat to compare the last time a pitcher threw a scoreless game when the team started the season 0-7. The answer that came back? 1915. They said the pitcher’s name, already lost to me, and then moved on like it didn’t matter.

But it did.

It reminded me of being a kid, sitting in the barber shop while my grandpa got his hair cut. On the table: a scattered mix of Playboys, crumpled copies of the Atlanta Journal Constitution, and thick baseball almanacs with more stats than a NASA flight manual. Those old timers could recall a batting average from 1951 like it was yesterday. Now? We have to Google a guy’s name just to remember if he still plays.

That’s when it hit me, that’s how I’d want to be remembered. Not with fireworks or statues. Just as some obscure footnote from the past that pops up when someone in the future is trying to make sense of their present. A tiny link in a long, unbroken chain. Doesn’t have to be an epic or saga written for my predominantly unremarkable life, just something. Just enough.

So there it is, I want to be remembered like one of those early 20th century baseball players. The ones with grainy black and white photos and strange nicknames like “Slats” or “Bucky.” Nobody really remembers them for who they were, but people still talk about them like they mattered. Not for glory but for spirit.

That kind of remembrance, that kind of quiet influence, being part of someone’s life without needing to be center stage. Legacy isn’t about being remembered by everyone. It’s about being remembered by someone, for the right reasons.

But I know the truth. Statistically, analytically, and existentially speaking: my name, my life, my so called legacy will one day be forgotten. Even in an age where we’re uploading more data per day than any civilization in history, the odds are still stacked against eternal relevance. At best, I’ll be a corrupted file on some long forgotten server. At worst, I’ll be erased before the dust settles.

And honestly... I’m okay with that. Not thrilled, let’s not pretend we don’t all secretly hope someone remembers us. That’s a human thing. A hope, not a flaw.

I know that when it’s my time, when the final curtain closes, I won’t be holding the pen anymore. There won’t be a say in how I’m remembered, or if I’m remembered at all. That’s where we leave legacy behind and meet death for what it really is.

After Death vs After Life

A clip of Keanu Reeves on a talk show made the rounds a while back. He was asked what he thought happens when we die. He didn’t flinch. He didn’t launch into theology or quantum speculation. He just said, “I know that the people who love us will miss us.” 15

That’s probably the most honest answer I’ve ever heard. No ego. No sales pitch. Just grief, plain and heavy. The simplicity of it is what gives it power. No promises, just presence. Just that quiet, devastating truth: you were here, and now you’re gone. And someone’s heart will never be the same.

And then there’s baseball.

Those of you who know me personally know I’ve always had a soft spot, (hell, a romantic heart) for the game. It’s my escape, my muse, and my quiet, guilty pleasure. A place where I can pretend, for just a few hours, that yelling at the TV and lining up my superstition laced good luck charms actually makes a difference. That maybe, somehow, I do have influence over a team I’m not even a part of.

Maybe that’s why this next story stuck with me, because beneath all the stats and superstition, baseball has always felt like something more.

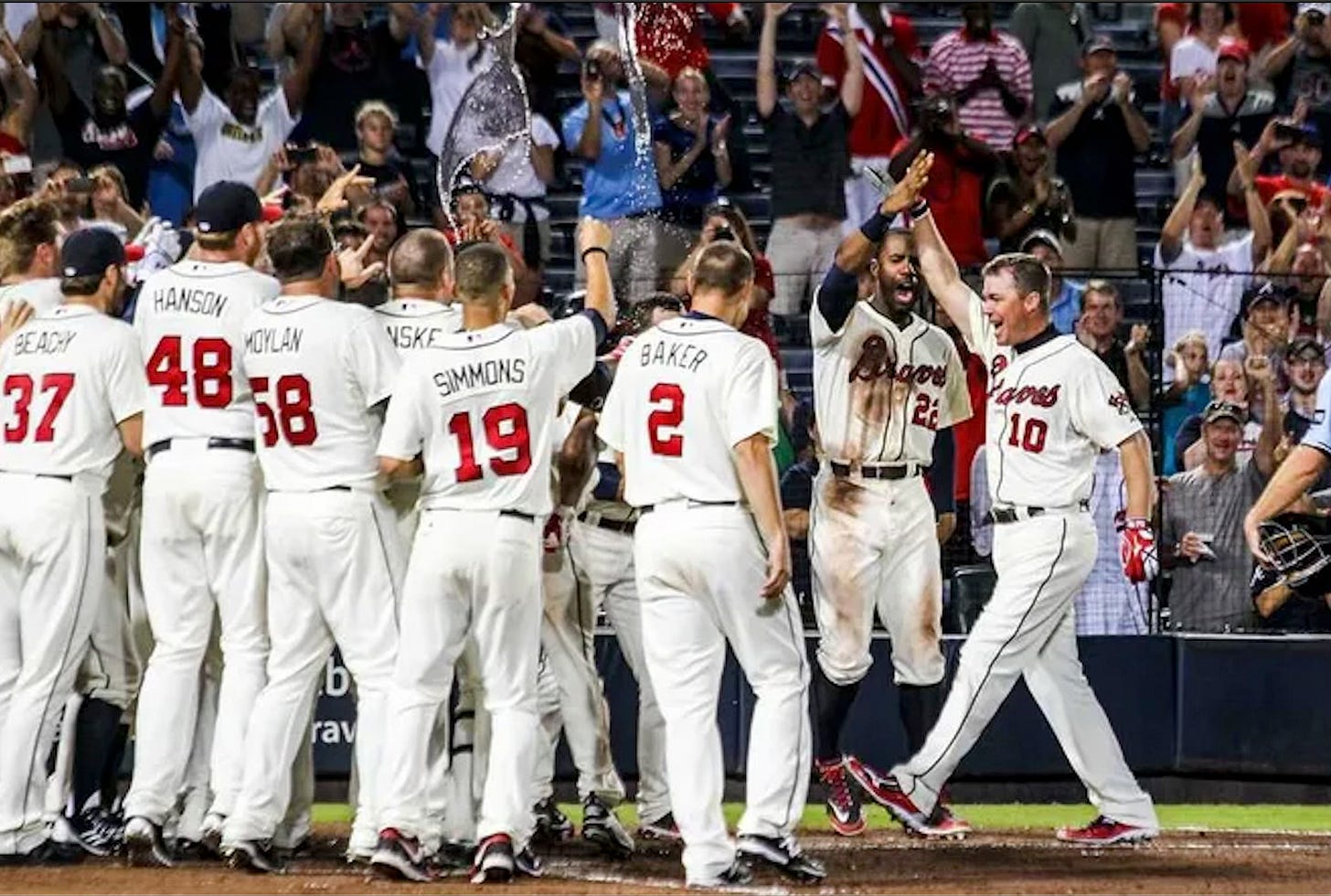

There’s a story floating around online about a baseball fan who collects images of walk off home runs. Not because of the stats. Not because of the game. But because, to him, those celebrations are a vision of heaven.

He collects pictures of hitters rounding third, arms outstretched, teammates spilling from the dugout, fans on their feet. That moment of eruption, the rush to welcome someone home. The way joy swells, raw and unrehearsed. It’s not just a win. It’s a return.

He was quoted as saying: “Look at the faces of his teammates waiting to welcome him. Look at their excitement. They can’t wait to celebrate with him. Look at the fans. Arms raised, big smiles, maybe even hugs for a perfect stranger.”16

Is it true? Probably not. Internet fiction, most likely. But it’s a damn good story. And for any baseball fan, casual or lifelong, it hits.

Still, there's a contrast hiding in that moment. While one man rounds third to the sound of roaring celebration, somewhere else, someone is grieving that home run. Someone is gripping the absence. The empty seat. The silence that follows. The stadium cheers, and a kitchen goes quiet. A jersey stays folded.

That’s the paradox: joy and sorrow, side by side. One person’s “welcome home” is another’s loss. And maybe that’s the most honest thing we can say about death. On one hand, it is nothingness. On the other, it leaves us behind with nothing but the echoes.

But even calling it “nothingness” feels wrong, because nothing is still something we can imagine. When we say "nothing," we picture darkness, silence, space. But real death, true death, is beyond that. It’s the absence of absence. The erasure of experience, thought, memory, time, sensation. Not silence, but the loss of the concept of sound. Not sleep, but the absence of dreaming, of self, of awareness that you ever were.

There’s no word for that. At least, not one that I have found.

It’s like trying to describe the color blue to someone born blind. You can circle around it, build metaphors and comparisons, but you’ll never land on it. Not really.

That’s why I think we dress death up in myths. That’s why we invent afterlives, gods, ghosts, and reasons. We can’t stand the idea that the lights just go out. That everything we ever were: every kiss, every scar, every secret, just disappears.

But maybe that’s the point.

For me, I don’t believe in an afterlife. No golden gates. No shadow realms. No great hall waiting with open arms and a flagon of mead. I don’t think there’s judgment, or a second round, or a reunion with lost brothers and family. But believe me when I say, I want to. I need to believe there’s something after death. It breaks a piece of my heart to admit I probably never will and to say out loud that I don’t believe there is.

I want to see the faces I miss. I want to wrap them up to laugh and sob. I want to meet the strangers I’ve read about, wrestled with through books and memories, and just sit with them awhile, no rush, just talk. I want to say I’m sorry to the ones who left before I could utter the words. I want to tell others how much I’ve missed them.

I want to scream at the ones like me, who stared at the phone with shaking hands but decided not to “bother anyone.” I want to tell how much pain they left behind when they quit the fight while they still had something left in the tank. I want to tell the ones I tried to save that I did my best. That I gave everything I had. But it wasn’t enough.

And I want, more than anything, to walk out onto a quiet Field of Dreams17. To play catch with the people I can’t anymore. To feel the pop of the glove and hear the sound of laughter that lives only in memory now.

I want all of that. With every ounce of my being. But my mind and my heart, they know: That will never happen. And somehow, I keep going anyway.

Maybe it’s just human nature. To want closure. To want forgiveness. To want just five more minutes. Because deep down, we don’t want nothingness. We don’t want the absence of self.

We want presence. Even if it hurts.

But here is the kicker. Maybe what gives life meaning isn’t that it lasts forever, but that it doesn’t. Maybe love matters more because we know one day it’ll end. Maybe the weight of existence is sacred because it's temporary. And maybe, just maybe, being missed is the only kind of immortality we’ll ever get.

Final Reflection

I’ve seen too much death in my life. But even saying that doesn’t feel fair.

What is too much death, compared to those who came before me? To the ones who had ten children knowing only three might survive? To those who buried names before they ever spoke a word? To the ones that watched their whole platoon whipped out in front of their eyes? To those that fought till the last breath, but lost anyways?

Still though, I feel it. I’ve seen too much. Been too close for comfort more times than I’d like to count. And even if that doesn’t make me an expert, it doesn’t make me a stranger to it either.

I don’t claim to have the clearest definition. But I know this, one day, I will die.

Maybe it doesn’t matter what happens after we die. No one really knows. That’s the trick, once you die, there’s no coming back to tell your story of the beyond.

Unless, of course, you watched late night TV in the ‘90s and early 2000s, back when there seemed to be a lot more “Stories of the Beyond” than there are today. Talk shows, psychics, reruns on the History Channel promising secret knowledge about the light at the end of the tunnel.

I think the real beauty of death isn’t in what it promises, but in what it demands of us while we’re still breathing. Death gives life its edges. Without it, we might drift endlessly, numb to the weight of time, disconnected from purpose. But knowing there’s an end forces us to care. To try. To love harder. To speak the words we’d otherwise keep buried. It forces us to show up, even when it hurts. Especially then.

If life went on forever, maybe none of it would matter. But it doesn’t. That’s the deal. That’s the absurd contract we’re all born into. The indifferent universe may not owe us meaning, but we still get to choose how we live inside it. And that choice, what we do with the moments between birth and death, is everything.

So no, I don’t know what comes after. I probably never will. But I know what’s here now.

I know the weight of a quiet morning. The taste of coffee you thought you’d never get to drink again. The warmth of a child’s hand in yours. The joy in embracing a long lost friend. The way laughter sounds when it’s earned, not given. The calm that settles in when she grabs your hand while the world screams in your ears. The ache that lingers when someone truly mattered.

And to me that’s more than enough.

Death may be the end, but it’s also the reason I’ve come to love being alive.

Author’s Note: This excerpt lives deep in the middle of my future book, but I thought it was relevant to this essay. The names don’t matter here. Just the weight.

The weight of his words drove me to the ground. Not physically. Not with force. But with the kind of gravity that only truth has, the kind that makes your knees ache and your chest hollow out before you even understand why.

He stepped closer. Quiet. Steady. The way old men walk when they’ve seen too much but still choose to carry what’s left.

Then he asked me, “When death calls your name, what do you hope to hear?”

I didn’t answer right away. Didn’t breathe. Didn’t blink.

Because the tears came first, not from sadness, but from a strange, sharp hope.

Like someone had finally given me permission to say the thing I’ve been dragging behind me for years.

So I replied, “When death comes and calls my name, I hope it says,

‘You can’t dodge me this time. You’ve always been so damn good at it. Slipped through places no one should’ve. But now… your time is up. It’s okay. Give me your ruck. Your fight is done.’

And I hope Death gives me a fist bump, like an old teammate would. One who saw the worst of it. One who understands why I’m so damn tired.

I hope Death crouches beside me, not in judgment, but in recognition. And says,

’You’ve carried enough. You fought with what you had left. You held the line when others fell. You did your best. I got it from here.’

And I hope Death promises,

‘Here, there is no noise. No weight. No more stone to push up that mountain. Here, there is quiet. Here, you can rest.’”

He didn’t respond. He just knelt down, eyes distant, but not hollow. Not with pity. Not even with comfort. But with something older than memory. A stillness that didn’t try to fix or explain.

It wasn’t kindness.

It was recognition.

I’ve got more excerpts lined up if that’s something y’all want to read. Let me know if you want me to keep mixing these in with the essays.

If there’s someone you know or if it’s you, going through hell, please reach out.

Don’t wait. Don’t hold it in. Don’t quit yet.

Trust me… it can get better. Maybe not all at once, but one breath at a time.

You’re not alone, even when it feels like it.

Here are some resources that might help:

Veterans Crisis Line

📞 Dial 988, then Press 1

Free, confidential support 24/7 for veterans, service members, and their families. Text, call, or chat, someone who gets it is always there.

Team RWB (Red, White & Blue)

Connects veterans to local communities through fitness, service, and leadership. It’s not therapy, it’s movement, purpose, and belonging.

The Semper Fi & America’s Fund

Provides direct support to combat-wounded, critically ill, and injured veterans and their families. Grants, resources, and long-term support from people who actually show up.

SOF Network

A trusted, private network built by and for the Special Operations community. They connect SOF veterans and families to vetted resources. Mental health, transition support, peer connections, and advocacy, without the red tape. Quiet professionals helping each other stay in the fight.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

📞 Helpline: 1-800-950-NAMI (6264)

🌐 nami.org

For veterans and civilians. Free resources, peer-led groups, and real conversations about mental health, no judgment, no agenda.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Medical examiners’ and coroners’ handbook on death registration and fetal death reporting. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Nasr, S. H. (2003). The heart of Islam: Enduring values for humanity. HarperOne.

Cioran, E. M. (1992). Drawn and quartered (R. Howard, Trans.). Arcade Publishing. (Original work published 1979)

Larrington, C. (Trans.). (2014). The Poetic Edda (Rev. ed.). Oxford University Press.

Camus, A. (1991). The plague (S. Gilbert, Trans.). Vintage International. (Original work published 1947)

Flower, H. I. (1996). Ancestor masks and aristocratic power in Roman culture. Oxford University Press.

Wiseman, T. P. (1995). Remembering the Roman people: Essays on late-Republican politics and literature. Oxford University Press.

Ikegami, E. (2005). Bonds of civility: Aesthetic networks and the political origins of Japanese culture. Cambridge University Press.

Bloch, M. (1971). Placing the dead: Tombs, ancestral villages, and kinship organization in Madagascar. Seminar Press.

Lomnitz, C. (2005). Death and the idea of Mexico. Zone Books.

Hutton, R. (1996). The stations of the sun: A history of the ritual year in Britain. Oxford University Press.

Lutz, D. W. (2010). The dead still among us: Victorian post-mortem photography and the aesthetic of mourning. In J. W. Hallam & L. Hockey (Eds.), Death, memory and material culture (pp. 45–62). Berg Publishers.

Cuevas, B. J. (2003). The hidden history of the Tibetan book of the dead. Oxford University Press.

Brandon Gaudin is an American sportscaster, currently serving as the television play-by-play announcer for the Atlanta Braves on FanDuel Sports Network South and Southeast.

The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. (2019, May 10). Keanu Reeves Has the Ultimate Answer for the Question of Life[Video].

Grind Athletics & Performance. (2024, January 15). I recently read about a man who collects pictures of hitters who hit walk-off home runs… [Facebook post].

Robinson, P. A. (Director). (1989). Field of dreams [Film]. Universal Pictures. A sentimental drama in which an Iowa farmer, played by Kevin Costner, builds a baseball field in his cornfield after hearing a mysterious voice. The film explores themes of reconciliation, memory, and the longing for connection with lost loved ones, making it a cultural touchstone for how we imagine the afterlife and second chances.

I think if life is finite it does inherently have more purpose than if its eternal. Assuming there is nothing after the end does lend much more weight to the time we are given. I do think its possible to live life with that level of intention with hope for the beyond. Its an unknowable thing. The irony being that you can't know until after you die. In which case, you cease to exist, or there is something more. Either way, I think there is wisdom in living life as fully as one can muster. For me, while I respect the reality of death, I think its a servant not a master. I believe that someone long ago conquered death. It still has its role to play, but it does so in the equality frame you described. It has no will, it has no discretion, it does as its told. By the master, the King. I think the efforts of every good life deserve that arrangement. Given what life can be, I think death is a mere spectator, relegated to a final, important task that it must perform endlessly, forever. Death, is the real loser here. It doesn't get a life, and from my view, it never even gets to end any.......

I, for one, want more of the book in any form you’re comfortable with